Across the sea: the distribution of Egyptian objects from British excavations to Australia and New Zealand

Over a two-week internship, I attempted to trace the scale of finds distribution from British excavations to Australia and New Zealand between 1880 and 1980 within the context of the larger global distribution network. Much of my time was spent sifting through the Petrie Museum’s archival holdings of distribution lists and other excavation documents (it is no small feat to read Sir Flinders Petrie’s handwriting!), as well as museums’ online collections in order to piece together separate accounts of the distribution of finds from archaeological sites in Egypt and their current locations in Antipodean collections. But in the course of my research, I found other acquisition paths than the ones described on the History of British excavation pages.

So far, eleven institutions across Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide in Australia, and Auckland, Dunedin, and Wellington in New Zealand were found to be connected in some way to British excavations in Egypt in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Adelaide, Australia, South Australian Museum

- Melbourne, Australia, Ian Potter Museum, University of Melbourne

- Melbourne, Australia, State Library of Victoria

- Melbourne, Australia, National Gallery of Victoria

- Melbourne, Australia, Museum Victoria

- Sydney, Australia, Museum of Ancient Cultures, Macquarie University

- Sydney, Australia, Australian Museum

- Sydney, Australia, Nicholson Museum, University of Sydney

- Auckland, New Zealand, War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

- Dunedin, New Zealand, Otago Museum

- Wellington, New Zealand, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The oldest institutions in Australia and New Zealand, in particular those in Melbourne, Sydney, and Wellington, paid a subscription to the Egypt Exploration Fund in exchange for a portion of the finds from excavations in Egypt as early as the 1880s. The newly established museums in colonial Australia and New Zealand were unable to compete with the financial contributions of their counterparts in the United Kingdom or the United States, and as a result sometimes they acquired objects by other methods. Correspondence between the Egypt Exploration Society and museum directors and curators indicate that museums might request certain kinds of objects, most often papyrus, or were sent out smaller finds, such as pottery fragments, as an act of goodwill.

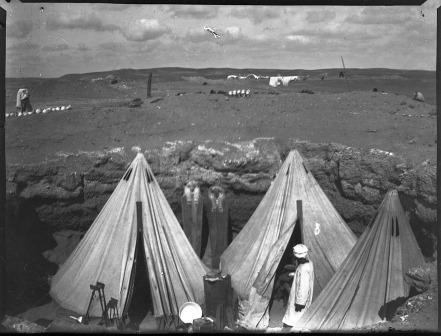

Although many of the Egyptian objects acquired from British excavations still remain in the same collection today, a large number were subsequently circulated, institutionally and commercially, through loans, deaccession and purchase, and donation. One fascinating example, is the Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne which holds a ‘Flinders Petrie Collection.’ A small donation of papyrus by the Egypt Exploration Fund began the collection in 1921. In 1957, two Australian brothers, Captain Edward Eustace and Everard Studley Miller, donated their private collection, which was obtained through Edward Eustace Miller’s participation on Sir Flinders Petrie’s excavations at Lahun, Gurob and Sedment during the 1920-21 season. Further Egyptian objects from British excavations were purchased for the University of Melbourne during the late 1950s from sales of recently deaccessioned objects from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

The story of the Ian Potter Museum of Art’s collection fits within a larger trend that saw the sharp decline in demand for Egyptian objects in the post-war, post-colonial years. During the 1960s and 1970s, Egyptian objects acquired from British excavations were subsequently moved between institutions or donated into collections, where the objects have since remained. The Australian Museum, Sydney, was found to have permanently loaned a large portion of their Egyptian collection to the Nicholson Museum, University of Sydney, and the Museum of Ancient Cultures, Macquarie University, in the 1960s. Likewise, as the Melbourne Public Library divided into three institutions (the State Library of Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and Museum Victoria) and its Egyptian collection was also divided. The circulation of objects and the organisational changes that took place in Antipodean museums in this period illustrates the ways these institutions negotiated the largely Eurocentric view supplied by the British Empire with a developing post-colonial self-identity.

The Antipodean chapter of finds distribution from British excavations in Egypt creates a vignette of the often complex afterlives of objects. By tracing the patterns of finds distribution to the Australia and New Zealand, it is possible to get a sense of the changing relationship between Britain, Australia and New Zealand, and how the evolution of archaeology and museums reflected changes in the geopolitical landscape of the time.

Katee Dean is a Classical Languages Honours graduate currently studying a Graduate Diploma in Museum Studies at The University of Queensland, Australia, and has worked in various roles at the RD Milns Antiquities Museum also at The University of Queensland. She has a strong research interest in Greek literature under the Roman Empire and the material culture of the ancient Mediterranean and Near East.

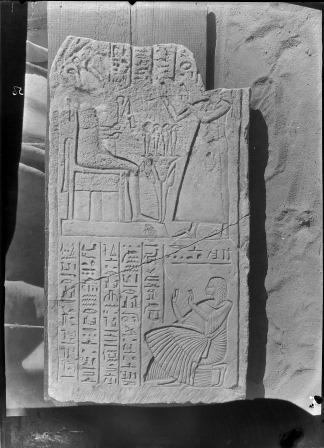

Stela of Nebuhotep found during the BSAE excavation at Sedment 1920-21 and now in the National Gallery of Victoria.

Petrie’s camp at Sedment where Captain Edward Eustace Miller worked in the 1920-21 season.

Katee in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology