Alice Geldart and the Egyptian Society of East Anglia (ESEA)

By Faye Kalloniatis

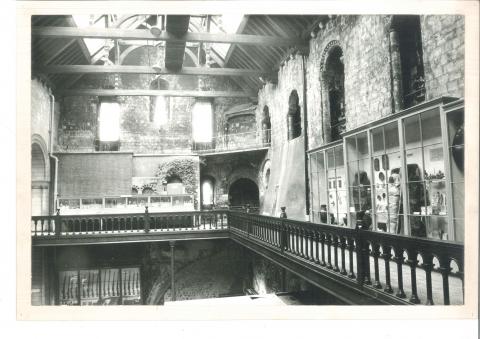

Egyptology in Norwich received an important boost during the first half of the 20th century through the establishment of a local organisation, the Egyptian Society of East Anglia. This Society, founded in 1915, became a focal point for Egyptological activity in the region and contributed in numerous ways towards raising the profile of that discipline. Its visibility within Norwich was helped by the fact that its ‘headquarters’ were located at Norwich Castle Museum. This created an informal partnership between both organisations and gave the Society access not only to the museum’s facilities but, more importantly, to its collections. In addition, the Society’s president – the Egyptian scholar, Dr Alyward M. Blackman – helped to raise ESEA’s profile and to closely align it with the Egypt Exploration Society, of which it was effectively a branch organisation.

As a focus for Egyptology, the Society offered several benefits and included an extensive programme of events as well as an avenue for its members to pursue their Egyptological interests. Moreover, it worked (successfully) towards attracting new ‘recruits’ and by extending its membership was able to increase its impact within Norwich and the surrounding region. However, without the enthusiastic and capable efforts of one individual – the honorary secretary, Alice Geldart – the Society could not have flourished as it did for over 25 years. Geldart worked energetically to foster the dual aims of the Society – to promote the study of Egyptology and to support Blackman’s research in Egypt. She appears to have been a modest individual but there is no doubt that she was a driving force behind the newly-formed organisation.

Geldart’s enthusiasm was evident in her support of a diverse range of educational initiatives designed to cater not only for the Society but also for the public in general. For the Society, Geldart helped to arrange regular talks by visiting speakers as well as Society members. She also organised a fortnightly study circle giving the chance for the local ESEA members to explore aspects of ancient Egyptian culture in greater depth, through study and discussion. Once topics were identified a syllabus would be set listing accompanying texts and other relevant materials – a task which often fell to Geldart. Over the years, the study circle covered a wide range of topics such as the evolution of the Egyptian house and temple, a history of the site of Amarna, and sessions in reading hieroglyphs, for which Geldart was one of the instructors. In fact, she on many occasions presented talks and gallery sessions for the study circle.

The Society’s programme also included visits to the private collections of some of its members. In 1917, the group was invited to view the Colman collection in Norwich, a collection of around 250 antiquities acquired at the end of the 19th century while the Colmans were in Egypt. Geldart not only organised the visit but she herself gave a talk highlighting some of the Colmans’ more interesting artefacts including the clay model granary, which she (rightly) described as ‘a rare specimen’. At around the same time, another member of the Society, Lady Boileau of Ketteringham Park, Norfolk, also invited the group to her ‘Gothic Hall’ to view her collection of scarabs and amulets. And in 1921, the group visited Ditchingham Hall, the home of Sir Rider Haggard best known as an author of novels belonging to the lost-world literary genre. Haggard was an Egyptophile who had made several journeys to Egypt and while there had purchased a substantial number of artefacts. His collection included a fine lapis lazuli swivel ring and a stelophorous statue, both of which he later donated to Norwich Castle Museum.

Alice Geldart’s focus was not limited to the Society. Much of her energy benefitted the public. She worked closely with the museum and contributed significantly to its educational programmes. She was frequently asked to give talks and/or gallery sessions; for instance, when the museum extended its opening hours to include Friday evenings it hoped that Geldart would give additional guided gallery tours such as she had successfully given on other occasions. She also participated in events organised by the museum but held at other venues. She helped organise a temporary Egyptian exhibition in Blackfriar’s Hall as part of Norwich Education Week and on another occasion she spoke at the Public Library on the excavated finds from Abydos.

She further sought to widen Egyptology’s reach within Norwich by proactively contacting a range of different groups, such as the College of Nursing, to invite them to the museum for sessions which could include talks, gallery visits and handling sessions (using duplicate objects). Nor did she limit herself to adult groups but was also keen to offer Egyptian sessions to children. She wrote to the local education authority to encourage schools to make museum visits. She once accompanied a group of youngsters from the Children’s Library to the museum and introduced them to the Egyptian gallery; and on another occasion she visited a school to give a classroom talk.

As a branch organisation of the Egypt Exploration Society, the local Society (ESEA) benefitted from the former’s distribution of excavated finds. These finds came largely from Abydos and Amarna and were sent to Geldart. At first they went to her home but eventually arrangements were made for the artefacts to be kept at the museum, where they did not remain ‘unused’. Geldart on several occasions organised and led sessions aimed at viewing and discussing them. Thus, these excavated finds became a valuable resource and extended the provision on offer to the Society’s members as well as to the museum’s visitors.

Another resource which the Society established was a library. Not only were the books kept on museum premises but the museum (as a sign of how much it valued ESEA’s contribution) assigned one of its own staff as librarian. Books could be borrowed or otherwise consulted within the museum and they proved invaluable for the previously-mentioned study circle topics as well as for private study.

Aside from all this activity, Geldart made generous financial contributions both to the local ESEA organisation and to the London-based Egypt Exploration Society. In fact, during several years (for instance, 1940 and 1941) her own, private, donation to the London Society amounted to the same as the subscriptions given to it by the full membership of the local ESEA.

In all of these ways, the tireless efforts of Alice Geldart on behalf of the local Society ensured that Egyptology enjoyed a greater presence within Norwich than it had previously had. Fortunately, Geldart’s work did not go unnoticed; it was applauded by the Society’s president, Aylward Blackman, who acknowledged that the local Society owed '. . . a deep debt of gratitude to Miss Geldart's great gift of organisation, her enthusiasm, and her power of communicating her enthusiasm to others.' A measure of her success was the extent to which ESEA increased its membership. Having started with around 30 members, within a few years it had grown to over 100. Perhaps the most striking proof of the extent to which Geldart had been the driving force was this – within months of her death in 1942, the Society folded and though the intention was to restart it at a later date, this never happened. The Egyptian Society of East Anglia had lost the one individual who had supported it and propelled it forward for over a quarter of a century.

Copy of hieroglyph worksheet used by members of ESEA’s study circle. Geldart was one of the instructors. © Norfolk Museums Service

The Egyptian gallery at Norwich Castle Museum in the 1930s. The local Society (ESEA) made valuable contributions to the development of the museum’s displays. © Norfolk Museums Service

Carrow House, the Norwich home of the Colman family. As part of its programme of visits, ESEA were invited here to view the extensive Egyptian collection which the Colmans later donated to Norwich Castle Museum. © Norfolk Museums Service