Objects from Petrie excavations in the Allard Pierson Museum. Results from the Petrie Perspective project

by Willem van Haarlem, curator of the Ancient Egyptian Department, Allard Pierson Museum

I. Inventory

The Allard Pierson Museum (APM) in Amsterdam holds a collection of objects acquired from W.M.F. Petrie’s excavations. It consists of objects that were transferred from the private Museum Scheurleer in The Hague, which was closed down in 1934; objects from the former Archaeological Institute of the University of Utrecht (where the Egyptologist Von Bissing was professor until 1926); and objects that were originally sent to the Municipal Museum in The Hague, and were later transferred to the APM.

The Museum Scheurleer was founded by the Banker Mr. C.W. Lunsingh Scheurleer in the 1920s. The correspondence between Scheurleer and Petrie shows that that in 1921 he requested to be a contributor to the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, explaining that he administered a museum-to-be that would be accessible to the public and that he wanted to expand the Egyptian collection. Petrie's draft reply shows that he agreed.

The objects allocated were transported in three different shipments from several BSAE- excavations to the Museum Scheurleer (PI, PII and PIII), and individually numbered from 1 to 350. In addition to an entry in the inventories each object had an individual label:

- PI (1-114, 1921) consisted of objects from Sedment (22 graves), Mayana (3 graves), Lahun (1 grave) and Gurob (2 graves). This was assigned to Scheurleer for his contribution of £ 25. The graves are dated to several periods

- PII (115-211, 1922) came from Abydos (38 graves) and Oxyrhynchus (1922). This for a contribution of £ 29 and four shillings.

- PIII (212-350, 1924) from Qau el-Kebir (24 graves), Badari (17 graves and two settlement contexts) and Hemamiya (12 graves). This following a contribution of £ 2 and two shillings in 1924, and a further additional payment of £ 20 in 1927.

There was an extra shipment in 1926 of a number of flint tools from the Fayum, Abydos and Qau el-Kebir (as PIV).

Scheurleer drew from multiple sources to acquire objects from excavations in Egypt for his museum and in 1922 he entered into a similar arrangement with the Egypt Exploration Society. By these means he acquired some necklaces and a bronze mirror from Abydos, and finds from the excavations at Tell el-Amarna.

Unfortunately in many cases objects from a single grave ended up in several places: the most striking example is grave 134 from Sidmant el-Gebel, from where objects have been dispersed to no less than 17 museums throughout the world. Apparently a part of the objects were simply left behind on the site without being documented. For example, from Sidmant el-Gebel 3683 finds are listed in total, while only 1323 are described and / or illustrated in the publications, notebooks and tomb cards. This is also evident from the Allard Pierson Museum collection which has a complete set of canopic jar lids from a grave in Sidmant el-Gebel, but without the accompanying jars they were once part of. Perhaps because no inscriptions were present, these were apparently not considered worth including. Objects were seen by many museums more individually with less attention to the context. This is reflected in much correspondence with recipients of objects, who could express preferences for object categories, which were often honored. The way in which in the past and present these things in museums were exhibited reflects these changing ideas and concepts.

Through the German Egyptologist and collector Von Bissing, who contributed to the excavations of Petrie as well, about 50 objects from these excavations ended up in the Museum Scheurleer, all from the Greco-Roman period, as part of the objects that Von Bissing deposited in the Museum Scheurleer. Between 1902 and 1912 von Bissing received those from the excavations at Abydos, Ehnasiya, Gheyta, Saft el-Henna, Memphis, Hawara and Tarkhan. Approximately half of these could be identified with the aid of published and unpublished sources.

II. What did Scheurleer intend with his museum and what was its national and international positioning?

The National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden was created at the instigation of King William I in the early 19th century. He desired his institution to equal the big archaeological museums that were then being created throughout Europe, such as the Louvre, the British Museum and the Berlin Museum. In contrast to these museums, however, the Leiden museum depended more on acquisitions from the art trade rather than directly from the field for its collections than the other museums. Only after Leiden museum started its own excavations in the 1950’s in Egypt, were substantial amounts of objects were transferred from there to the Netherlands, such as from Abu Rowash.

The Museum Scheurleer was quite successful in its acquiring for its collections, in particular by (temporarily) housing the Von Bissing Collection. It also received objects directly from excavations in Egypt, as described above. Scheurleer wanted his collection to strengthen and emphasize the position of The Hague as Royal Court and Residence City, the seat of the government and international legal institutions (the Peace Palace was a neighbor), also vis-à-vis the Leiden Museum, which Scheurleer considered to be a sleepy and not very dynamic institution. Unfortunately, this was all cut short after when he was declared bankrupt in 1934.

III. The missing objects

40 objects are unaccounted for: 8 pieces of jewellery, 3 bronze objects, 1 stone vase, one pair of ivory sticks, and 27 pieces of pottery; two objects disappeared in the Allard Pierson Museum during WW II. Between the closure of the Scheurleer Museum and transfer to the Allard Pierson Museum in 1934, these must have disappeared.

According to the inventory of the 78 objects in the Municipal Museum which acquired these after the closure of the Museum Scheurleer, none of the missing objects are included there. The mystery remains, because of a number of missing objects (13) the labels are preserved, which should have stayed with the objects. Furthermore, there are 22 original Scheurleer inventory cards Scheurleer of the missing pieces preserved in the APM, partly overlapping with the labels.

The former Museum Scheurleer building in the 1920s.

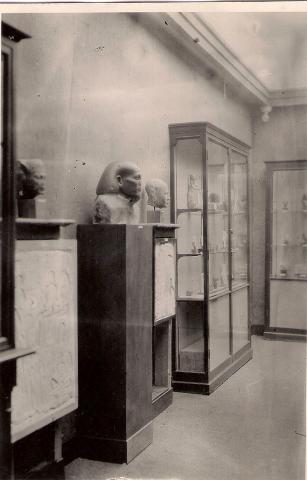

Inside former Museum Scheurleer in the 1920s