Monsieur Henri Bach: a third-generation Gladstone in British Egyptology

By Maarten Horn

The name Henri Bach may not strike a note with many but his contribution to Egyptology as a less-visible fieldwork assistant was nonetheless substantial. If ‘Henri Bach’ rings a bell to some, the name Gladstone surely calls to mind British politics – not Egyptology? As one of many Western people involved in past British-led archaeological fieldwork in Egypt, Bach’s name features in an extensive list of such participants compiled by the Artefacts of Excavation project. Whilst some of these names link through to short biographies, others lead to pages where such details are lacking. This blog post is meant to help fill in the blank of Henri Bach, a fieldwork assistant whose name you may stumble upon in archaeological reports or other published or archival material, but a person who remains obscure all the same. Often referred to as Monsieur Henri Bach, this little biography considers how a Frenchman’s entry into British Egyptology at UCL and British-led digs in Egypt was part of a broader involvement of the Gladstone family. If anything, I hope to show how past practices of accrediting Western excavation members can enable us to do archival research into and gain more knowledge about these people’s lives. Yet, this ability also exposes the failings of these practices: how their embeddedness in colonialism and orientalism equally led to the anonymization and lasting obscurity of most Egyptian excavation members.

Charles Henri Gladstone Bach was born 6 March 1898 in Lyon, France, the only child of the French Lutheran Bishop Henri Bach (1853-1933) and the British Elizabeth Augusta Gladstone (1858-1941). The Bach family likely relocated to Paris around 1900, when Henri Bach took up the role of ecclesiastical superintendent at the Church of Saint Jean on 147 Rue de Grenelle, which also acted as their place of residence – with the Eiffel Tower right around the corner. Not much is known about Henri Junior’s early life. He attended the École Alsacienne in Paris before being drafted into the French army on 16 April 1917 in the throes of the First World War. Bach, barely 19, would serve for three years in heavy artillery regiments, attaining the rank of Marshal of Lodgings before his discharge on 28 May 1920. A few months later he was off to London to study Egyptology under Professor W.M. Flinders Petrie at UCL. What inspired him to leave his family and country behind to pursue this rather specific ambition?

In my archival research of Henri Bach, I was fortunate enough to get in touch with his son Jean (via the kind help of his daughter Sophie) who very generously supplied me with further details about his life. Unfortunately, I am given the impression of a man who, later in life, had become very reserved and did not like to dwell on the past. His time in Egypt was almost never raised, perhaps, as Jean suggests, out of nostalgia. Jean is in the dark of what might have sparked his father’s interest in Egyptology but speculates it might have been a trip to Egypt undertaken by his mother Elizabeth (and his father?), who was fascinated by ancient Egypt. In fact, he informs me, Elizabeth knew Petrie well. The roots of their acquaintance may be found in the person of Elizabeth’s father, John Hall Gladstone (1827-1902). A British chemist and Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution, he was also known for his religious work and involvement in the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

But he also represents the first-generation Gladstone to be drawn into Egyptology. As early as 1889, he was asked by Petrie to study metal finds from his excavations in Egypt, starting a collaboration that would last until the end of his life. During his introductory lecture as UCL’s new Edwards Professor of Egyptology in 1893, Petrie thus highlighted Dr Gladstone’s work in helping to identify a copper age in Egypt.

A second generation may be spotted in 1896, when Petrie accredits a “Miss Gladstone” for her help in drawing objects from Naqada and Ballas in his eponymously titled publication. Though her identity remains uncertain, Dr Gladstone had several daughters who might fit this bill. Some may be less likely, such as Elizabeth’s half-sister Margaret Ethel (1870-1911), more renowned perhaps as the wife of Labour Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald. Others, however, are more plausible as early and long-time subscribers to the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE). Its financial reports frequently mention Madame Bach (Gladstone), a Miss Gladstone, and Basil Holmes in their lists of subscribers. The second of these was likely Elizabeth’s sister Florence May (1855-1928), who made a final subscription in 1928, the year she passed away (as indicated in the financial report). She was a historian of Kensington, the author of Aubrey House, Kensington, from 1698 -1920 (1922) and Notting Hill in bygone days (1924). Both Elizabeth and Florence were also amateur artists, making either of them possible as Petrie’s drawing assistant.

Though their sister Isabella Matilda (1861-1949) also held historical interests, as evidenced by her early book The London burial grounds (1896), by 1896 she had already married Basil Holmes (1856-1940), secretary of London’s Metropolitan Public Gardens Association (in which Isabella acted as an honorary secretary), as well as councillor for Ealing North before taking on the role of alderman in 1925. In addition to being a subscriber to the BSAE, Holmes also became an executive member on the BSAE’s general committee in or around 1920, the same year Henri started his London studies.

In light of the foregoing, Henri’s move to UCL starts to make sense; Petrie and Egyptology had ever surrounded and impressed on him as he grew up. Whilst in London, Henri stayed with his aunt Florence on 46 Ladbroke Grove in Notting Hill. Over the course of two academic years, he enrolled into several classes but did not pay to obtain the College Certificate in Egyptology. He withdrew in 1921-22 but continued to participate in fieldwork abroad. From his first year at UCL, he had joined Petrie on his BSAE excavations at Sedment (1920-21), as well as at Abydos and Oxyrhynkhos (1921-22). The next seasons saw him accompany Guy and Winifred Brunton in their BSAE fieldwork at Qau-Badari (1922-24) and their British Museum digs at Mostagedda (1927-28) and Matmar (1929-30). Guy Brunton’s reports speak very highly of Bach: from an able and devoted BSAE field assistant to being their “old friend [who] volunteered to spend the winter with us, his experience and skill being of the greatest value”. His work included the recording of graves, surveying, plan drawing, and assisting Guy Brunton in photography. But he was also put in charge at Mostagedda when Brunton undertook a few weeks’ worth of work in the Fayum for the Oriental Institute of Chicago in January 1928. If Brunton’s name adorns the reports, its contents are a legacy of a much wider archaeological community of practice, including Western field assistants such as Bach and his less valued Egyptian co-workers.

Matmar would mark the end of Bach’s archaeological career. Back in Paris, he volunteered for charities and on 12 April 1932 married Irene Gabrielle Simone Moser, with whom he would have five children. In the meantime, he had turned his attention to library studies, to which he devoted two publications in 1931: L’organisation des bibliothèques paroissiales and Guide du bibliothécaire amateur. The latter became a standard work through its multiple re-editions by Yvonne Oddon under the new title Petit guide du bibliothécaire.

Bach also wrote on religious matters, such as Notre Église: Sa Foi et son Organisation (1935). After the Second World War, he worked in a bookstore before joining the Librairie Protestante in Paris until his retirement. He died 9 February 1976 in Boulogne Billancourt, France.

I would like to thank Jean and Sophie Bach, as well as Jake Holmes for their help in providing information about and images of the people discussed here.

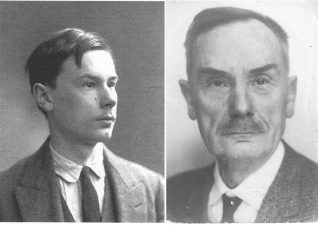

Figure 1: A younger and older Charles Henri Gladstone Bach. Courtesy of Jean Bach

Figure 2: John Hall Gladstone (1868). Courtesy of Jake Holmes

Figure 3: Elizabeth Augusta Bach Gladstone and Florence May Gladstone (1880). Courtesy of Jake Holmes

Figure 4: Isabella Matilda Holmes Gladstone (1895) and Basil Holmes (c. 1876). Courtesy of Jake Holmes

Figure 5: “Bach taking measurements for the map” with Egyptian co-workers at the background. Photograph taken at Qau from Henri Frankfort’s 1922-23 photo album. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society