What the Faiyum? The excavations of the Graeco-Roman branch of the EEF

A casual perusal of the excavation seasons page or the site guide page of this website will reveal a lot of place names which have the word ‘Faiyum’ in parenthesis. Yet sometimes that same location already has a site guide dedicated to it without the Faiyum being attached to it (as is the case of Ihnasya, Saft el-Hinna or Sedment).

So why are these sites designated differently? And what is the Faiyum?

The Faiyum is a large fertile area southwest of Cairo, about 65 kilometres east to west in size, that contains a large lake. The increased access to water allowed for substantial agricultural use. The region was particularly exploited in the Graeco-Roman period, and became a popular location for new settlements for Macedonian and Greek veterans who were awarded land under Ptolemy II and III. The designation ‘Faiyum’ distinguishes the excavations undertaken by the Graeco-Roman branch of the EEF, which had very different aims and objectives from other British excavations and excavators.

The original mission of the EEF was to investigate classical and biblical sites. Chance finds of papyri during the course of those early British excavations intrigued classical philologists who saw new literary and documentary works being found that could further shed light on the lives of people in the ancient world. The Graeco-Roman branch of the EEF was born on 1 July 1897 ‘for the discovery and publication of the remains of classical antiquity and early Christianity in Egypt’ and their excavations centred on the Faiyum. The unique environmental conditions of the Faiyum allowed for the preservation of relatively intact organic material for thousands of years. Moreover, the high concentration of later settlements meant that the detritus of everyday life was preserved in the rubbish heaps outside the towns or as part of the base material that made up the cartonnage wrappings of mummies which were often made from recycled papyrus documents.

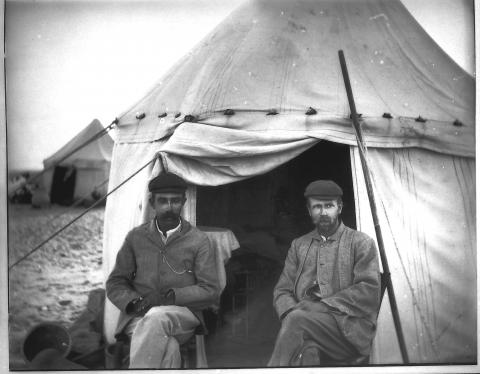

The Graeco-Roman branch excavations were led by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt. Both men had a mercenary attitude to archaeological remains that were not papyri and a loose idea of the developing scientific methodology of archaeology. As far as they were concerned/For them, rubbish heaps and burial sites were important only for the documents that might be recovered. Other objects that might be recovered were afterthoughts as was any sort of semblance of documentation or excavation methodology. Their brief season accounts in the Archaeological Reports are remarkable for the tunnel-like concentration on the papyri and its overall condition. For instance, 150 graves would be cleared in little more than a week and the site would be abandoned if the conditions meant that the papyri were too damp to be handled. Little thought would be given to the overall site and limited respect conferred to the bodies that might be wrapped in the precious texts.

On account of Grenfell and Hunt’s efforts (and a few others), the Egyptian Exploration Society owns about half a million texts, which represent the largest collection of papyri in the world. These texts are housed in the Sackler Library at the University of Oxford and provide an extraordinary snapshot into the ordinary lives of Egyptians from the early Ptolemaic to the Fatimid era. The first volume of papyri was published in 1898 and papyrologists continue to publish documents what were discovered over 100 years ago.

Grenfell and Hunt in the field. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society.